This week’s guest is Lee Einsweiler of Code Studio in Austin, Texas. We talk about all things land use and zoning — what goes into a land use code, the approaches to zoning in different countries, and of course the dreaded topic of parking.

Showing posts sorted by date for query parking. Sort by relevance Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by date for query parking. Sort by relevance Show all posts

Sunday, August 6, 2017

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

A Changing Mobility Structure and The Death of Parking

Thanksgiving

It was probably pretty common to argue about politics over Thanksgiving weekend with your families. I got into a discussion about parking. And yes I told them this might be on the blog. My parents live close to a town in California called Walnut Creek. It's a compact walk-able center for shopping in the San Francisco Bay Area and very walk-able when you get out of the car.

But you have to get there first. The BART station was built too far away from downtown for it to be ultimately useful as a shaper of parking policy and the Macy's parking lot is soon going to be charging for the privilege of storing a vehicle while you shop. I have no doubt that free parking will continue to exist, however this argument might not have even been taking place in 20-30 years.

The Death of a Parking Space

Currently there is a call to hold horses on parking development due to the coming revolution of autonomous vehicles. Quotes from articles on news sites go like this...

I also had former Madison Mayor Dave Cieslewicz on the podcast recently and he lamented the focus on parking and told members of the audience who were revitalizing storefronts to just wait to build new parking. Below is the shorter snippet on his relevant comments.

"I would not be investing in parking at all, for at least five years. Let's just see how it plays out"

Others are noticing what Dave and planners are starting to say out loud.

A Future of Autonomous Vehicles

I would very much like to ban driving from dense urban cores. With adequate subway, bus, and delivery systems, there would be no need for small vehicles that only carry one or two people to be so hulking and wasteful. And perhaps it will end up like Ghent, in Belgium.

Imagine how many people could move without a metal frame surrounding them? What could be done with all that parking we free up? There is more than enough space in cities today to make room for everyone. It doesn't even have to look like the densest places of our wildest dreams or nightmares. It could be cozy. And supported by a good transportation system.

Three Ways of Autonomy

Another article that I read recently discussed the three ways of future autonomous cities. In a report put together by McKinsey and Bloomberg, a typology of places was put forth to describe how cities will adopt autonomy.

I know that car companies don't see this human centered future. Yonah Freemark documented this idea of heaven and hell. They see the money that can be made selling a car, or a car service, or anything that will make for exchanging currency. But who knows what the future brings. I'm just watching for the trends. We might want to start thinking of what we want the future to look like though before it looks at us.

Back to Thanksgiving

So back to Thanksgiving and Walnut Creek. This discussion about a need for parking wouldn't happen in 20 years. We won't have to worry about cars crashing over sidewalks and won't have to pay for parking. And the goods we buy can be delivered to our door Just another sunny day in California.

That is....if we get the policy right.

It was probably pretty common to argue about politics over Thanksgiving weekend with your families. I got into a discussion about parking. And yes I told them this might be on the blog. My parents live close to a town in California called Walnut Creek. It's a compact walk-able center for shopping in the San Francisco Bay Area and very walk-able when you get out of the car.

But you have to get there first. The BART station was built too far away from downtown for it to be ultimately useful as a shaper of parking policy and the Macy's parking lot is soon going to be charging for the privilege of storing a vehicle while you shop. I have no doubt that free parking will continue to exist, however this argument might not have even been taking place in 20-30 years.

The Death of a Parking Space

Currently there is a call to hold horses on parking development due to the coming revolution of autonomous vehicles. Quotes from articles on news sites go like this...

This from an article in the Atlanta Business Journal about how technology is going to change real estate development. But that is a future prediction. But what about now? In Houston, it's already real...slightly.“The flow of any retail follows the function of parking,” explained Weilminster at the Nov. 9 event at the Grand Hyatt in Buckhead. Self-driving cars are also expected to reduce the need for parking decks, which cost between $25,000 and $40,000 per parking space to build.

City officials are somewhat reluctant to attribute the loss to any one cause, but data show parking meters along Washington and nearby began pulling in less money per month right around the time paid-ride companies such as Uber and Lyft entered Houston in February 2014....

Meanwhile, sales tax collections in the district appear unaffected by the parking rules, based on city data.According to the Houston Chronicle, parking lots that would usually support revelers are used less based on the data. Of course we don't know if its directly because of ride hailing services, but it would be a good hypothesis.

I also had former Madison Mayor Dave Cieslewicz on the podcast recently and he lamented the focus on parking and told members of the audience who were revitalizing storefronts to just wait to build new parking. Below is the shorter snippet on his relevant comments.

"I would not be investing in parking at all, for at least five years. Let's just see how it plays out"

Others are noticing what Dave and planners are starting to say out loud.

"They’re saying, 'Don’t build parking lots, don’t build garages, you aren’t going to need them,'" said Councilman Skip Moore, citing city planners at national conferences across the country....

...significant pressures are aligning which should give pause to investors in automobile parking garages. Garages are typically financed on a 30-year payback, either by cities or private investors. But they could find themselves holding the un-payable back-end of a 30-year note, when folks stop driving within the next 15 years...Even technology VCs are getting in on the action. Marc Andreesson said this to The Verge.

There are mayors that would, for example, like to just declare their city core to [ban] human-driven cars. They want a grid of autonomous cars, golf carts, buses, trams, whatever, and it’s just a service, all electric, all autonomous. Think about what they could do if they had that. They could take out all of the street parking. They could take out all of the parking lots. They could turn the entire downtown area into a park with these very lightweight electric vehicles.He also talks about flying cars for high end users which makes me think that autonomous vehicles will be on the surface with the plebes and flying cars will be for the "landed gentry" as it were. I'm starting to see the Jetsons come to life in my head right now. Or maybe the Star Wars planet of Coruscant where the lower to the ground you live, the lower your social status.

A Future of Autonomous Vehicles

I would very much like to ban driving from dense urban cores. With adequate subway, bus, and delivery systems, there would be no need for small vehicles that only carry one or two people to be so hulking and wasteful. And perhaps it will end up like Ghent, in Belgium.

“It was a rather radical plan to ban all cars from an area of about 35 hectares,” recalls Beke. “With every decision you take, there can be some opposition – but I never expected a bullet, of course.”

There were protests outside Ghent’s city hall: businesses were afraid they’d lose their customers, elderly residents were concerned about being cut off from their children. But Beke stood his ground, and although a few businesses that relied on car access had to move, today the city centre is thriving.Or maybe we'll have a new paradigm with moving sidewalks or those tubes from the Futurama cartoon. Though that seems like a lot to maintain and we know how often elevators break down at subway stops. But imagine if arterials were just moving walkways?

Imagine how many people could move without a metal frame surrounding them? What could be done with all that parking we free up? There is more than enough space in cities today to make room for everyone. It doesn't even have to look like the densest places of our wildest dreams or nightmares. It could be cozy. And supported by a good transportation system.

Three Ways of Autonomy

Another article that I read recently discussed the three ways of future autonomous cities. In a report put together by McKinsey and Bloomberg, a typology of places was put forth to describe how cities will adopt autonomy.

Cities like Delhi, Mexico City, and Mumbai ("clean and shared" category) will focus on the EV part of the equation in an attempt to reduce pollution...I think typologies are a great way to break down ideas but this is a bit too simplistic given what we discussed earlier about pedestrian central cities and the reduced parking possibilities. I think we'll see a mixture of these things based on urban form and pedestrian policy. And it's possible there will be pockets of pedestrian oasis free from big vehicles all together that aren't a part of central cities. That is if we get policy right.

...Meanwhile, a second type of city characterized by sprawl (think L.A. or San Antonio) will still privilege personal, private car ownership, even if "autonomy and electrification allow passengers to use time in traffic for business or pleasure."...

...But a third type—densely populated, high-income places like Chicago, Hong Kong, London, and Singapore—will move away from private car ownership toward shared AV mobility, the report says. People may travel more overall, because picking up an Uber AV will be relatively cheap and easy...

I know that car companies don't see this human centered future. Yonah Freemark documented this idea of heaven and hell. They see the money that can be made selling a car, or a car service, or anything that will make for exchanging currency. But who knows what the future brings. I'm just watching for the trends. We might want to start thinking of what we want the future to look like though before it looks at us.

Back to Thanksgiving

So back to Thanksgiving and Walnut Creek. This discussion about a need for parking wouldn't happen in 20 years. We won't have to worry about cars crashing over sidewalks and won't have to pay for parking. And the goods we buy can be delivered to our door Just another sunny day in California.

That is....if we get the policy right.

Friday, October 28, 2016

Podcast: Meea Kang on Developing Affordable Housing in California

This week I’m joined by Meea Kang, Rail~volution board member and founding partner of Domus Development. I caught up with Meea at the Rail~volution conference to talk about what it’s like to be an affordable housing developer building sustainable projects. We discuss the 16 variances needed to do transit-oriented development in Sacramento, workforce housing in Tahoe on a bus line with 60-minute headways, and what it takes to pass a state law that reduces parking requirements near transit.

Wednesday, November 11, 2015

Most Read from November 10th

Here are Yesterday's Top Stories from The Direct Transfer Daily

Image via Lyft

- "Dallas doesn’t principally have a parking problem. It has a downtown Dallas problem"

- LA City Council will have to revote on mobility plan, critics hope it's their chance.

- Maybe Lyft only wants to be friends with rail lines, not buses? That's what the image says to me

Bonus Quote

"This experience has let me know that architecture can speak to and touch people and change things, regardless of what academia or what the old guard may want you to believe"

- Germane Barnes

- "Dallas doesn’t principally have a parking problem. It has a downtown Dallas problem"

- LA City Council will have to revote on mobility plan, critics hope it's their chance.

- Maybe Lyft only wants to be friends with rail lines, not buses? That's what the image says to me

Bonus Quote

"This experience has let me know that architecture can speak to and touch people and change things, regardless of what academia or what the old guard may want you to believe"

- Germane Barnes

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

The Cost of Street Parking Spaces

Cities are adding bicycle lanes to streets with heavy bike traffic as a means of improving safety, but the process is constantly being hindered by strong opposition from the businesses along the streets where the lanes are proposed. Most small businesses with street parking spots are reluctant to give them up for parking lanes out of fear that decreased parking space will affect their business.

This was recently highlighted in San Francisco, when bike lanes were proposed for Polk Street. Though Polk was considered one of the most dangerous streets in the city for cyclists and pedestrians, the plan to add a bike lane faced heavy backlash from local merchants, and as a result, took over 2 years to implement. The backlash from local merchants provoked enough contention in bike advocates that some started a Yelp campaign against an optometrist who lobbied the Mayor to remove his block from the Polk Street bike lane plan.

However, the fears of bike lanes damaging local business are unfounded. In fact, many studies show that rather than decreasing business, increased bike traffic actually seems to promote more spending. While people in cars tend to spend more money per shopping trip, people on bikes tend to take more trips and will ultimately spend more. This has been seen in cities throughout the US and internationally, so any opposition to bike lanes based on negative economic impacts have yet to be justified.

Bike lanes aren’t the only use for parking spots that can be good for business. Parklets are popping up in front of stores and restaurants in many cities, and they too, can increase sales for nearby businesses. Parklets take up only one or two parking spots, but their occupancy rate and turnover are far higher than a parking spot. As a result, places that install parklets often find that the extra activity promotes extra business.

This was recently highlighted in San Francisco, when bike lanes were proposed for Polk Street. Though Polk was considered one of the most dangerous streets in the city for cyclists and pedestrians, the plan to add a bike lane faced heavy backlash from local merchants, and as a result, took over 2 years to implement. The backlash from local merchants provoked enough contention in bike advocates that some started a Yelp campaign against an optometrist who lobbied the Mayor to remove his block from the Polk Street bike lane plan.

However, the fears of bike lanes damaging local business are unfounded. In fact, many studies show that rather than decreasing business, increased bike traffic actually seems to promote more spending. While people in cars tend to spend more money per shopping trip, people on bikes tend to take more trips and will ultimately spend more. This has been seen in cities throughout the US and internationally, so any opposition to bike lanes based on negative economic impacts have yet to be justified.

Bike lanes aren’t the only use for parking spots that can be good for business. Parklets are popping up in front of stores and restaurants in many cities, and they too, can increase sales for nearby businesses. Parklets take up only one or two parking spots, but their occupancy rate and turnover are far higher than a parking spot. As a result, places that install parklets often find that the extra activity promotes extra business.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

How Self Driving Cars Will Change Our Cities

Self-driving cars are getting a lot of publicity--and for good reason.

Some think that driverless cars will completely reshape our cityscapes. With fewer traffic accidents due to human error, autonomous vehicles would change the car repair and insurance industries. Ride-hailing companies like Uber and car-share companies like Zipcar could be transformed. One of the biggest changes, however, will be that cities won’t need nearly as many parking facilities. While there will still be a place for private car ownership, many major cities will end up having surplus parking space that can be turned into parks or even repurposed for new commercial uses.

But no matter how transformative they are, autonomous cars are unlikely to replace mass transit. One big reason is because mass transit is simply more efficient in terms of density. In cities, where space is both limited and expensive, a bus or train that can carry dozens or even hundreds of passengers will always be more efficient in terms of space and cost. And because more and more people are moving to cities, the real innovation that may come out of autonomous vehicle technology might not be the cars, but self-driving buses. After all, the US road system was built for cars, and it works just as well for buses.

Some experts fear that self driving cars will promote sprawl. Long, arduous commutes incentivize living near urban centers, but if commuting by car became much easier, the allure of city life might give way to the appeal of lower costs and bigger homes in suburbs. Many projections estimate that self driving cars could roll out as soon as the early 2020s, and since we’ve seen the effects of sprawl on health and economic mobility, it’s a big concern that planners will need to deal with soon.

Sunday, March 1, 2015

Podcast: Ann Cheng Discusses GreenTrip

This week on the Talking Headways podcast, Ann Cheng from Transform joins me to talk about how developers can lower their parking obligations through Green Trip, a certification program for development in the Bay Area.

~~~

Need more news about cities daily? Sign up for the Direct Transfer.

~~~

Need more news about cities daily? Sign up for the Direct Transfer.

Thursday, February 5, 2015

When You Can Put a Face to Hardship

I always marvel at the generosity of people when it comes to strangers. But especially to strangers who are shown to have a hardship on television or in the news. So it came as no surprise this week that a Detroit man, James Robertson, who travels almost a marathon every day gets the attention of folks who really want to help.

I would however love to see the demographics and opinions of those generous people. Perhaps the biggest thing I would ask is...

"Do you support paying more in taxes for a better transit network?"

The reason I would ask this questions is because while in urbanist circles we understand the connection between housing and transportation costs and supply and demand for affordable housing (apparently though in SF we still don't get it) I wonder how much people actually do understand.

There's always so much push back to giving "those people" access but when there is a face put to the masses, they are more charitable with their money and time.

And people put up over $260K for a car for James, but that money would probably fund a few bus routes for more than just one person.

I think Ben Adler at Grist puts it best when he says:

There was a great City Metric piece recently on this issue. They explain how much transit means to EU economies. It's pretty huge.

But not just that, it's about access, just like in James' case.

Check out the piece, it makes a compelling case for other co-benefits as well. And if you want a US case, just check out New York.

And sure, we can connect people with cars. But there's a tax on that. There's roads to build, parking to provide and upkeep to the car for each individual. And if you're sitting in traffic, your time is a tax.

James couldn't keep his car running because it cost too much. But he and others wouldn't have to worry about that if they are paying into a larger system. One where everyone benefits, not just those who happen to have a car.

~~

Consider joining The Direct Transfer, news on cities daily!

I would however love to see the demographics and opinions of those generous people. Perhaps the biggest thing I would ask is...

"Do you support paying more in taxes for a better transit network?"

The reason I would ask this questions is because while in urbanist circles we understand the connection between housing and transportation costs and supply and demand for affordable housing (apparently though in SF we still don't get it) I wonder how much people actually do understand.

There's always so much push back to giving "those people" access but when there is a face put to the masses, they are more charitable with their money and time.

And people put up over $260K for a car for James, but that money would probably fund a few bus routes for more than just one person.

I think Ben Adler at Grist puts it best when he says:

Only in America would we assume that Robertson’s 46-mile commute is the natural order of things and the problem is that some people don’t have cars. Robertson’s situation demonstrates that low-income residents of Detroit and other cities around the U.S. need two things: mass transit and affordable housing near jobs.So what do we need to do to educate people about this? How do we explain the concept of economic competitiveness and access?

There was a great City Metric piece recently on this issue. They explain how much transit means to EU economies. It's pretty huge.

In fact, the sector accounts for €130-150bn of the EU’s GDP each year, as well as providing 1.2m jobs and indirectly creating the conditions for an estimated 2-2.5m more.

But not just that, it's about access, just like in James' case.

That’s why, in London, one of the major advocates for the soon-to-be completed Crossrail project was the business sector: it realised that investment in public transport is key to matching employers with appropriately skilled employees, and retailers with customers.

Check out the piece, it makes a compelling case for other co-benefits as well. And if you want a US case, just check out New York.

The more jobs you can reasonably commute to within an hour, the more job opportunities you'll have, and the higher your wage will be.

...

In New York, mass transit is the path to economic mobility, not education, It’s far more important to have a MetroCard than a college degree.

And sure, we can connect people with cars. But there's a tax on that. There's roads to build, parking to provide and upkeep to the car for each individual. And if you're sitting in traffic, your time is a tax.

James couldn't keep his car running because it cost too much. But he and others wouldn't have to worry about that if they are paying into a larger system. One where everyone benefits, not just those who happen to have a car.

~~

Consider joining The Direct Transfer, news on cities daily!

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Talking Headways Podcast: Speeding By Design

This week my guest host Tim Halbur and I chat about how we set speed limits, the design of complete streets for trucks, and the airbnb-ification of parking spaces. You might also hear some stories about selling parking spaces to fund parties. Listen in below.

Friday, August 1, 2014

Is Good Urban Form Slowing Us Down?

There has been a lot of chatter recently on the issue of fast vs slow transit. This week is the perfect time for this discussion as two major United States transit projects of differing stripes opened up; the Metro Silver Line in Washington DC and the Tucson Streetcar.

Last week, Yonah Freemark wrote a post discussing the benefits of fast transit specifically calling out the Green Line in Minneapolis for running 11 miles in about an hour. Now, this line has parts of what people are always asking streetcars to have; dedicated lanes. "They get stuck!" Yet this line, as well as the T-Third in San Francisco and others mentioned in the post are still "too slow". Yonah goes on to discuss metro expansion in Paris leaving a discussion of politics and costs of rapid transit to the very end.

To me this points to the first place where urbanism and fast transit disagree with each other, block sizes and stop spacing. By trying to maximize connections to the community, the transit line has to stop more often, slowing speeds. And if built into a legacy urban fabric, this also includes negotiation with tons of cross streets where designers don't give priority to the transit line. This happens in Cleveland on the Health Line BRT as well as the Orange Line in Los Angeles, even though it has its own very separated right of way. The Gold Line Light Rail in LA and the Orange Line originally had the same distance, yet one was 15 minutes faster end to end. A lot of this had to do with less priority on cross streets given to the Orange Line, not because it was a bus or rail line.

We continue to talk as if dedicated lanes are magic, but its a suite of tools that helps speed transit along inside of our wonderful urban fabrics. Transit is directly affected by urbanism, if we let it be.

But then there is the other side of this discussion. Transit's effect on urbanism. Some New Urbanists believe that slow transit is necessary for building better urbanism. Rob Steuteville of New Urban News calls this "Place Mobility". The theory goes like this:

To increase the viability of streetcars in a world dominated by a "cost effectiveness" measure dependent on calculations of speed, the "Trip Not Taken" was refreshing. Many transit lines were being built without regard to neighborhood or were cheap and easy. But they were fast! You can see how the "cost effectiveness" measure intervened with elevated rail through Tyson's Corner (yes I'm still annoyed) or the numerous commuter rail lines on freight rights of way in smaller regions that probably should never have been built. But they were fast!

Yes the streetcar helps with creating place in the minds of developers and urban enthusiasts, but no it doesn't do the whole job. The Pearl District and Seattle's South Lake Union were perfect storms of huge singular property ownership, massive investments in additional infrastructure, proximity to a major employment center, lack of NIMBYs, and a strong real estate market. But look at the results. It's hard to argue that the streetcar didn't help develop this massively successful district in one of planning's favorite cities. But it's also hard to give it all the credit.

The crux of the argument is that place making should be the ultimate goal and slowing things down makes things better. And many cities see the streetcar as some sort of fertilizer that makes it grow and a reason to change zoning code. Because of very stringent local land use opposition (read NIMBY), this makes a lot of sense. If a streetcar can lead to the restructuring of land use or the fulcrum of a district revitalization, I see that as a benefit. But again, don't give it too much credit.

From a safety standpoint this slowing down idea makes sense. The Portland Streetcar has been in collisions, but no one has died or been seriously hurt, unlike a number of high profile collisions in places like Houston, where drivers can't seem to follow the rules. Our society also puts up with over 30,000 deaths a year to get places faster on interstate highways as well.

But...

Ultimately the base success of a transit line isn't in the amount of development it has spurred or the zoning it has changed. It's the ability to get a lot of people where they want to go, in a timely fashion. A commenter on Jarret Walker's Human Transit Blog says it best.

But if we are going to spend so much money, we might as well figure out a way to transport the most people possible. Sometimes that might be streetcars. Other times it's not.

But back to urbanism and transit.

In Portland, dedicated lanes on the North/South parts of the line wouldn't make as much difference because it has the same issues we mentioned with the Green Line above and narrow streets. Streetcars have to deal with urbanism. I think streetcars are ok as a circulator in downtowns, because these are the trips that help people get around dense places that are proximate. You can bring your groceries on when its raining and disabled folks can load their wheelchairs with dignity. Tourists like the certainty of the tracks and little kids love the ride. We see that even on 20 minute headways, 13,000 riders are on the line every day. It's hard to argue with that, given it's more riders than many first choice bus lines in some major cities without rail.

However for linear route based transit operations, we need dedicated lanes and signal priority to at least make the expenditure worthwhile and play nice with our urbanism. Once you get outside of a district, people want to get places. I like subways and wish we had more, but it seems politics and money seem to get in the way like Yonah mentions above. Some might even argue that before we even think about building fixed guideway lines, we should focus on our buses. Perhaps we should have a threshold system ridership before putting in rail, to determine whether all options for increasing ridership have been exhausted. Houston's new network plan could be a good guide. And personally, I don't think BRT should be special. It should be the norm. Luckily the new 5339 bus facilities funding guidance could allow for BRT and Rapid Bus funding (they are NOT the same thing).

But there's a new report out which discusses which factors drive ridership for fixed guideway transit once we decide to go that route. Employment and residential density around transit lines, the cost of parking downtown, and grade separation were found to be the most effective measures when put together to drive ridership according to a recent TCRP report released earlier this month. Individually employment had an r squared of .2 while the others had negligible impacts. Only taken together as a whole did these measures drive the most ridership as seen below.

The report goes on to say "The degree of grade separation is likely influential because it serves as a proxy for service variables such as speed, frequency, and reliability that may lead to greater transit ridership."

But determining success is hard. In fact, its so hard that of the transit projects surveyed, the only thing that transit agencies seemed to agree on (it has dots in every project below) was that the line would be cheap! We discussed this briefly above.

So all of this is to say that Streetcars are not the worst transit ever and urbanism will affect transit, and transit will affect urbanism. We just need to decide what the appropriate ways are for intervention such that we maximize people's ability to get to the places they want to go and build great communities. Let's not swing the pendulum too far to either side, it might tip the balance against us.

Last week, Yonah Freemark wrote a post discussing the benefits of fast transit specifically calling out the Green Line in Minneapolis for running 11 miles in about an hour. Now, this line has parts of what people are always asking streetcars to have; dedicated lanes. "They get stuck!" Yet this line, as well as the T-Third in San Francisco and others mentioned in the post are still "too slow". Yonah goes on to discuss metro expansion in Paris leaving a discussion of politics and costs of rapid transit to the very end.

To me this points to the first place where urbanism and fast transit disagree with each other, block sizes and stop spacing. By trying to maximize connections to the community, the transit line has to stop more often, slowing speeds. And if built into a legacy urban fabric, this also includes negotiation with tons of cross streets where designers don't give priority to the transit line. This happens in Cleveland on the Health Line BRT as well as the Orange Line in Los Angeles, even though it has its own very separated right of way. The Gold Line Light Rail in LA and the Orange Line originally had the same distance, yet one was 15 minutes faster end to end. A lot of this had to do with less priority on cross streets given to the Orange Line, not because it was a bus or rail line.

We continue to talk as if dedicated lanes are magic, but its a suite of tools that helps speed transit along inside of our wonderful urban fabrics. Transit is directly affected by urbanism, if we let it be.

But then there is the other side of this discussion. Transit's effect on urbanism. Some New Urbanists believe that slow transit is necessary for building better urbanism. Rob Steuteville of New Urban News calls this "Place Mobility". The theory goes like this:

When a streetcar -- or other catalyst -- creates a compact, dynamic place, other kinds of mobility become possible. The densest concentrations of bike-share and car-share stations in Portland are located in the area served by the streetcar. That's no coincidence. You can literally get anywhere without a car.In Portland parlance, this is the "Trip Not Taken". When you build up the urban fabric of a city, many usually induced trips disappear. That car trip to the grocery store becomes a walk and that streetcar trip to Powell's Books might be a bike trip now. Or in the world of the web, that trip might change hands, from you to the delivery truck. In Portland at the time they calculated a 31 million mile reduction in VMT from the housing units built along the streetcar route.

To increase the viability of streetcars in a world dominated by a "cost effectiveness" measure dependent on calculations of speed, the "Trip Not Taken" was refreshing. Many transit lines were being built without regard to neighborhood or were cheap and easy. But they were fast! You can see how the "cost effectiveness" measure intervened with elevated rail through Tyson's Corner (yes I'm still annoyed) or the numerous commuter rail lines on freight rights of way in smaller regions that probably should never have been built. But they were fast!

Yes the streetcar helps with creating place in the minds of developers and urban enthusiasts, but no it doesn't do the whole job. The Pearl District and Seattle's South Lake Union were perfect storms of huge singular property ownership, massive investments in additional infrastructure, proximity to a major employment center, lack of NIMBYs, and a strong real estate market. But look at the results. It's hard to argue that the streetcar didn't help develop this massively successful district in one of planning's favorite cities. But it's also hard to give it all the credit.

The crux of the argument is that place making should be the ultimate goal and slowing things down makes things better. And many cities see the streetcar as some sort of fertilizer that makes it grow and a reason to change zoning code. Because of very stringent local land use opposition (read NIMBY), this makes a lot of sense. If a streetcar can lead to the restructuring of land use or the fulcrum of a district revitalization, I see that as a benefit. But again, don't give it too much credit.

From a safety standpoint this slowing down idea makes sense. The Portland Streetcar has been in collisions, but no one has died or been seriously hurt, unlike a number of high profile collisions in places like Houston, where drivers can't seem to follow the rules. Our society also puts up with over 30,000 deaths a year to get places faster on interstate highways as well.

But...

Ultimately the base success of a transit line isn't in the amount of development it has spurred or the zoning it has changed. It's the ability to get a lot of people where they want to go, in a timely fashion. A commenter on Jarret Walker's Human Transit Blog says it best.

But the romantic impulse towards slow transit wears away quickly if you have no choice but to rely on it all the time! I don't have a car, so I rely on buses that travel excruciatingly slowly, wasting much of my time.As someone who has gotten rid of my car and considers myself a walking, bike riding, transit loving (and sometimes zipcaring) urbanist, I find it very annoying that it takes an hour to go three miles here in San Francisco on the bus. And if I need to get downtown, I take the Subway which is a half mile away versus the streetcar which is half a block away because time does actually matter. We see this decision play out every day when people choose to drive cars over using transit.

But if we are going to spend so much money, we might as well figure out a way to transport the most people possible. Sometimes that might be streetcars. Other times it's not.

But back to urbanism and transit.

In Portland, dedicated lanes on the North/South parts of the line wouldn't make as much difference because it has the same issues we mentioned with the Green Line above and narrow streets. Streetcars have to deal with urbanism. I think streetcars are ok as a circulator in downtowns, because these are the trips that help people get around dense places that are proximate. You can bring your groceries on when its raining and disabled folks can load their wheelchairs with dignity. Tourists like the certainty of the tracks and little kids love the ride. We see that even on 20 minute headways, 13,000 riders are on the line every day. It's hard to argue with that, given it's more riders than many first choice bus lines in some major cities without rail.

However for linear route based transit operations, we need dedicated lanes and signal priority to at least make the expenditure worthwhile and play nice with our urbanism. Once you get outside of a district, people want to get places. I like subways and wish we had more, but it seems politics and money seem to get in the way like Yonah mentions above. Some might even argue that before we even think about building fixed guideway lines, we should focus on our buses. Perhaps we should have a threshold system ridership before putting in rail, to determine whether all options for increasing ridership have been exhausted. Houston's new network plan could be a good guide. And personally, I don't think BRT should be special. It should be the norm. Luckily the new 5339 bus facilities funding guidance could allow for BRT and Rapid Bus funding (they are NOT the same thing).

But there's a new report out which discusses which factors drive ridership for fixed guideway transit once we decide to go that route. Employment and residential density around transit lines, the cost of parking downtown, and grade separation were found to be the most effective measures when put together to drive ridership according to a recent TCRP report released earlier this month. Individually employment had an r squared of .2 while the others had negligible impacts. Only taken together as a whole did these measures drive the most ridership as seen below.

The report goes on to say "The degree of grade separation is likely influential because it serves as a proxy for service variables such as speed, frequency, and reliability that may lead to greater transit ridership."

But determining success is hard. In fact, its so hard that of the transit projects surveyed, the only thing that transit agencies seemed to agree on (it has dots in every project below) was that the line would be cheap! We discussed this briefly above.

"Provide fixed guideway transit in corridors where inexpensive right of way can be easily accessed"Which is many times why we end up with slow transit. It's cheap. We're cheap. Streetcar costs are below that of light rail or subways and since its in a mixed traffic right of way, it will be cheaper politically than BRT. Commuter rail on freight rights of way is the best to them though even though its the worst at creating ridership. To me it's is even cheaper because it usually ignores the chart above with the focus on employment and residential density.

So all of this is to say that Streetcars are not the worst transit ever and urbanism will affect transit, and transit will affect urbanism. We just need to decide what the appropriate ways are for intervention such that we maximize people's ability to get to the places they want to go and build great communities. Let's not swing the pendulum too far to either side, it might tip the balance against us.

Thursday, December 5, 2013

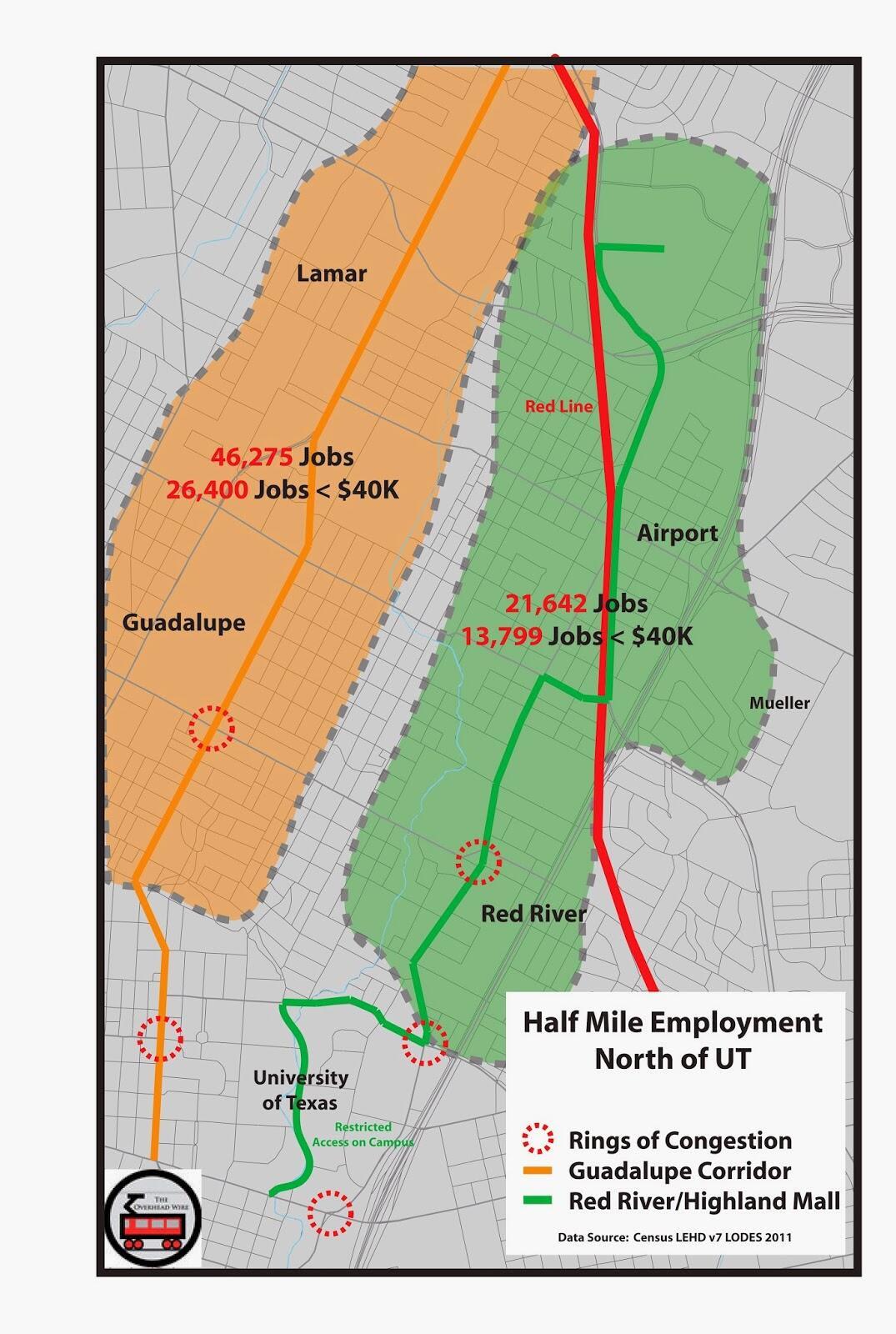

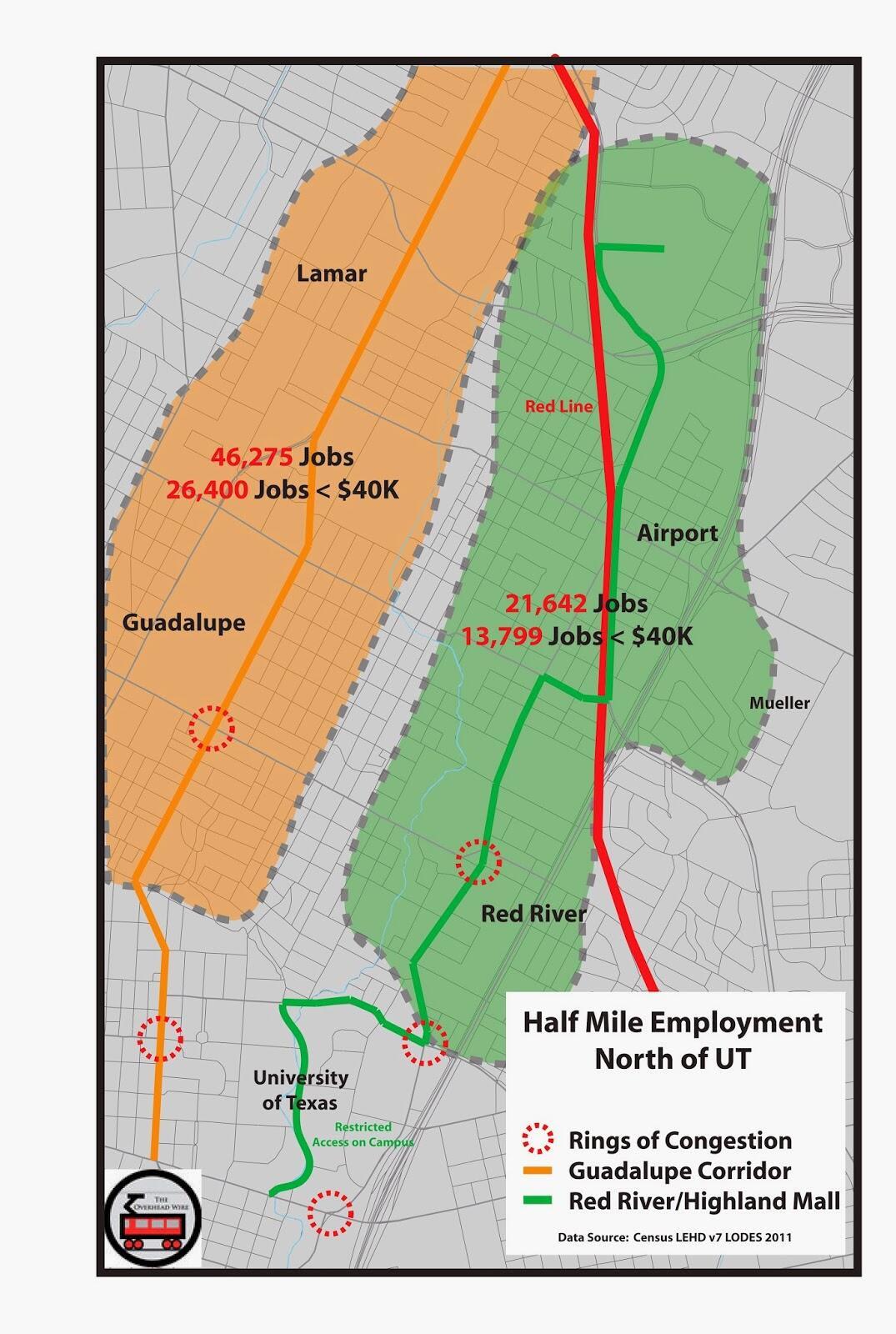

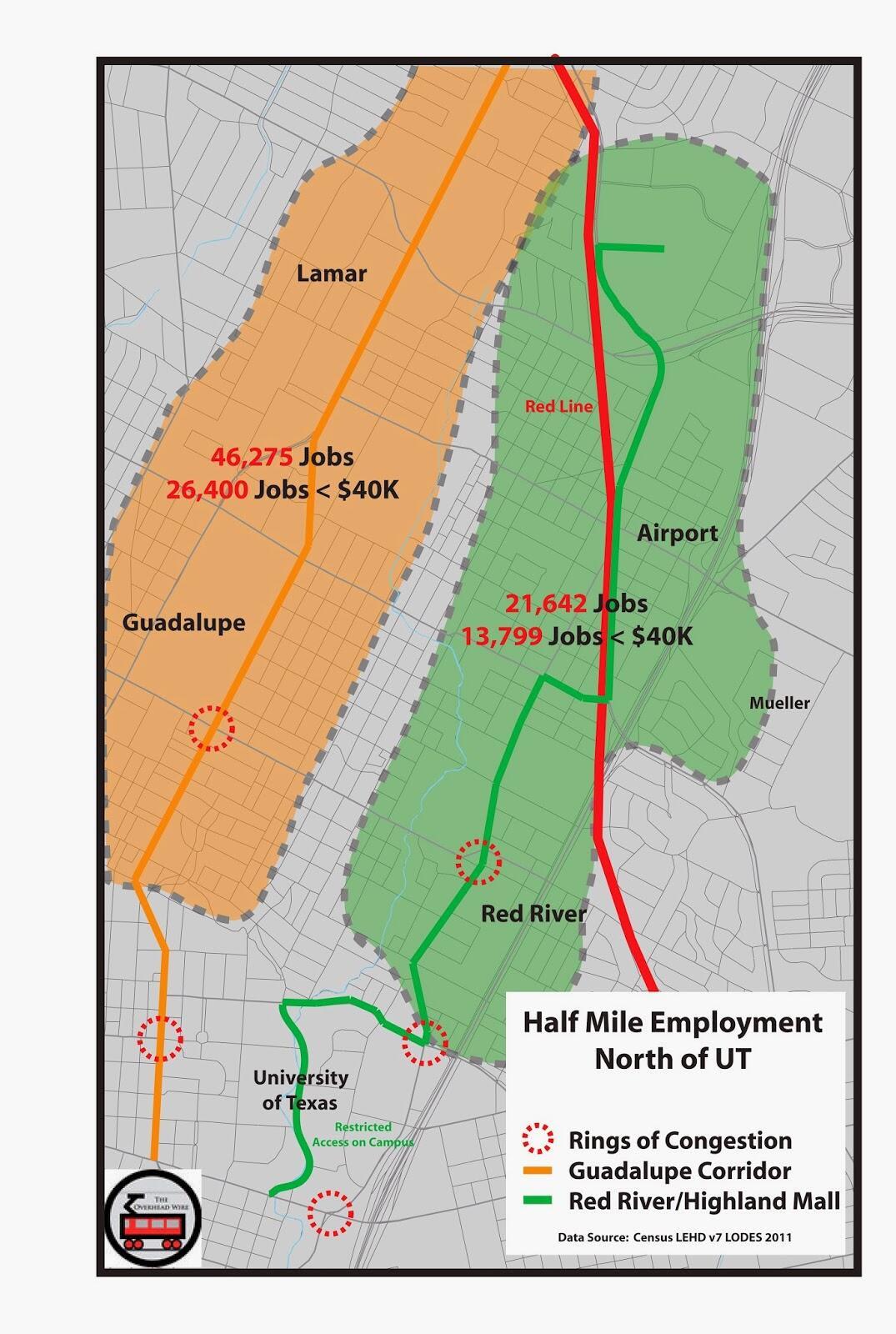

My Basic Reasons Why I like a Guadalupe Lamar Alignment

While I don't quibble with the need for expanded capacity on Riverside, I will argue that Guadalupe/Lamar is a superior route for urban rail in north of Austin's core, over a possible Highland corridor. I'll let others deal with the methodology issues in Project Connect's selection process, but for me, the data is clear that this corridor is superior for the following reasons...

While there are many laudable goals for building urban transit including housing and office development, the main reason for building a rail line is to increase the capacity of a road such that more people can get into a constrained space. Dan Chatman at the University of California at Berkeley and others have found that rail's key economic development benefit is serving to increase agglomeration effects in employment centers.

This is currently happening in the Warner Center in Los Angeles and Tyson's Corner in Virginia. The constraint to employment center growth is limits on auto access, so now landowners and policy makers introduce high capacity transit to get more people of all skill levels to their jobs and to increase the public and private productivity of the land.

This goal is in tandem to providing affordable housing, mixed income housing,

and reducing transportation costs but ultimately it is one of the main

reasons to build transit, to continue the increased benefits that

downtown's economic engine brings to the city and region as a whole

while giving more people access to those benefits.

So if the core is constrained, what is the best way to make travel easier to the most people such that they can reliably access jobs in the core as it grows? In other words, how do we feed more oxygen into the fire. Austin's current bus network does a good job of this, but certain corridors are constrained and need to be expanded. But you can't expand roads in those corridors so you need to expand the number of people who can travel in those corridors, hence high capacity transit.

So if the core is constrained, what is the best way to make travel easier to the most people such that they can reliably access jobs in the core as it grows? In other words, how do we feed more oxygen into the fire. Austin's current bus network does a good job of this, but certain corridors are constrained and need to be expanded. But you can't expand roads in those corridors so you need to expand the number of people who can travel in those corridors, hence high capacity transit.

2. RIDERSHIP

The answer to where you'll be able to pull the most oxygen to feed the fire is where they will be the most riders. Riders matter for two reasons, first it makes your line more cost effective from an operational standpoint. Currently the highest ridership bus line in the city by a long shot is the #1 on Guadalupe and Lamar. According to data from the service plan 2020 report, this corridor suffers the most in terms of on time performance. In fact that 2010 report noted that the bus was on time only 49% of the time!

The answer to where you'll be able to pull the most oxygen to feed the fire is where they will be the most riders. Riders matter for two reasons, first it makes your line more cost effective from an operational standpoint. Currently the highest ridership bus line in the city by a long shot is the #1 on Guadalupe and Lamar. According to data from the service plan 2020 report, this corridor suffers the most in terms of on time performance. In fact that 2010 report noted that the bus was on time only 49% of the time!

But the more riders you have on the line, the more you

can justify per passenger the operational cost. Portland has done a

great job with their light rail cost efficiency and has proved many

times that compared to the bus network, the light rail network is a more

efficient way of moving people in and out of downtown.

The second reason ridership matters is that if

you're going to be seeking funding from the FTA, you're also going to

be competing against every other region in the country seeking federal

funds. In the Transit Space Race report I noted that it would take 78

years to fund all the lines that are being planned with the current

federal funding levels of $1.6B per year. That number has actually been

lowered because of a stingy congress, but it's still a very small

number, especially when you're helping to build multi-billion dollar

subways in New York and San Francisco.

So what is the best way to win funding? In part its selling to the FTA that you have all your land use planning in place and have thought a bit about economic development. But they want to give a project justification rating, an overall rating, and you have to compete with lines like the LA downtown connector that are projecting 16,000 new trips out of 88,000 riders.

So what is the best way to win funding? In part its selling to the FTA that you have all your land use planning in place and have thought a bit about economic development. But they want to give a project justification rating, an overall rating, and you have to compete with lines like the LA downtown connector that are projecting 16,000 new trips out of 88,000 riders.

I highly recommend taking a look at other projects that are ahead of Austin in line for federal funds. Also, going back in time, the Austin line in 1999 scored very

high against places that are now built including Houston and the Twin

Cities - The Lamar line, which had pieces of the current Metro Rail line would have had 37,000 riders.

So what is the biggest thing that any light rail line can do to get more riders? Connect people with jobs.

3. THE IMPORTANCE OF JOBS

Connecting jobs with

transit drives ridership. We know this from research done by Zupan and

Pushkarev, Gary Barnes, and UC Berkeley's TOD guru Robert Cervero.

Considering over 59% of transit trips are for work, this becomes an

important point.

Pushkarev and Zupan in 1977's Public Transit and Land Use Policy - "Enlarging downtown size or raising nearby residential density. Suppose

the options are to double the size of a downtown from 10 to 20 million

square feet, or to double the residential density within a few miles of

it from 15 to 30 du/acre. The former will increase per capita trips by

transit three to four times more than the latter." Many more can be found in this post on the blog

This from Gary Barnes - "Using regression analysis, he showed that in Minneapolis, aside from

developing residential densities, transit share can be increased by

building up commercial centers. In the regression, he showed that for

every 1000 people per square mile that the residential density grew, the

increase in transit's share to downtown increased 2.4% versus .6%

increase when people went to suburban jobs."

So what does this tell us? That trips increase when you connect places of density in a city to a strong downtown. But it's not just downtown that matters, it's all jobs along a line that build ridership. I created this chart below from my TRB paper on light rail ridership. It shows new light rail lines that were built in the last 10 years. What makes their ridership go up? Connections to jobs. Now in the paper I discuss many of the other issues that folks above mention as well including restricted parking downtown. But jobs seems to be a clear cut connection that's fairly easy to see, and backed up by a lot of the literature.

So jobs matter for ridership, and connecting more jobs within

a half mile of stations will get you more riders. So ignoring the core

of UT, Capital Complex and downtown, where are the most jobs outside of

downtown in the northern corridors that are being compared. Well of

course on the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor. This data was taken from the

2011 census LEHD dataset. The North Lamar corridor to Crestview has at

this present time 46,275 jobs within a half mile. 26,400 of them are

people making less than $40k annually. Contrast that with a likely

Highland Corridor, and you see less than half the number of jobs. Even

with rosy projections and development on that corridor, where would

25,000 jobs come from?

This

is part of the reason people are so upset at the process and

selection. Sure it's about congestion and redevelopment and serving low

income communities. But congestion is where the jobs are located. Redevelopment actually happens on light rail proximate to jobs as well.

4. WHERE DEVELOPMENT HAPPENS ON LIGHT RAIL

We

know this because CTOD did a study called Rails to Real Estate, which

looked at development patterns along three new light rail lines in

Charlotte, Denver, and Minneapolis. What this report says is that light

rail doesn't just create ridership out of thin air, a lot of public

policy has to take place but also that the market drives a significant

pattern of development.

There

are maps in the report that show where development happened along these

lines, but its best to describe it as the employment gravity well.

Basically the market for denser development is in major employment

centers, and that market gets extended from the gravity well by the rail

line. It's not just downtown because Denver's line connects the Tech

Center, which is the second largest employment cluster in the region,

and it saw an uptick in development as well. Take a look for yourself.

Alignments go away from downtown from left to right.

This is obviously a small sample size of new lines but it

is quite instructive. The location of major employment drives

development and redevelopment because the transit is extending the

market, not creating it. Putting a line up into the Highland sector

might help spur a small catalyst of development, but its proximity to

downtown or a major employment center that matters most. Guadalupe and

Lamar have much more employment along the corridor which is likely to

give more people more options to connect with places they work and

places they want to go. But it's the straight line that matters a lot

too.

5. BE ON THE WAY

Anyone who knows Jarrett Walker's work knows that he likes transit lines to be straight. This causes less

schedule disruption and makes the line faster and more reliable. In the

back and forth on twitter he noted the jagged lines that would likely

occur if we built the Highland line, especially the section through UT.

You can see in the map above how hard it would be to get from one point

to the other without having to make turns somewhere. But its not straight.

Additionally, we know from UC Berkeley's research that

for people to use the train, employment is best closer to the stop, than

further away. People are more likely to use transit for work if it's

within a quarter mile, while taking it from their homes is likely to be

acceptable to walk a half mile. This means the route that travels

through a less used part of UT, by all the parking garages near the

Capital (even though there will be a med school there) and less inviting

pedestrian places like Airport Blvd, is less likely to drive

ridership. Now this might be redeveloped in the future. But we know

where people go now, because they take the #1 bus to get there.

So this is my case. As a national transit

advocate, bad decisions in locations make it harder for us to fight for

more funding against those who oppose us. Killer ridership lines are

great for beating back the forces against us as well as giving future

leaders support for expansion.

Remember

1. The Core is Constrained

2. Ridership Matters for Operations and Funding

3. Ridership is Tied to Employment Location and Density

4. Development and Redevelopment Happens Near Jobs Now

5. The Straight Line is the Best Line

Saturday, January 12, 2013

Grating on a Curve

I was in Houston for a work meeting last spring and went on a tour with our good friend Christof Spieler who has taken a hiatus from blogging

at CTC Houston while he is an active member of the board for Houston

Metro. He was kind enough to take me around to a lot of the new

construction going on to complete Houston's three newest light rail

lines. I must say I was blown away at the progress and opportunities

that the system holds.

Houston's Light Rail Plans via Christof Spieler

I know there is a lot of consternation in Houston from certain congressional parties that if they had it their way would never have let the city build its first line. But I'm sure glad they did because it's allowed them so much political support to push forward with the system they are installing now. While even that had its fits and starts as well as issues with general managers and vehicle orders, I firmly believe that this will be the most European system in the United States when completed.

North Corridor Construction

Unlike any other LRT system in the United States, they eschewed existing freight rights of way and made the conscious decision to run in the major corridors with dedicated guideways. This is going to bring unprecedented mobility to the newly served areas as well as perhaps a few issues as well.

While many say that Houston has no zoning, what it really means is that Houston has no use restrictions. Unless your neighborhood has existing deed restrictions, anything is fair game as long as it pencils in your pro-forma. Making that pro-forma more difficult is all of the setback and parking regulations that are required from the city. It costs a lot of money and changes development dynamics but the lack of use restrictions allow development such as the housing below. Townhouses on small lots that would never have been allowed in any other single family neighborhood.

Southwest Corridor in East Downtown (EDO)

This also raises the issue of affordable housing. While the lack of building restrictions keeps prices fairly low, extremely low in fact when compared to SF or NYC, it doesn't mean that neighborhoods won't see some drastic changes coming to their neighborhoods.

If you would like to see a few more of the images from the trip, check out my Flickr page

Houston's Light Rail Plans via Christof Spieler

I know there is a lot of consternation in Houston from certain congressional parties that if they had it their way would never have let the city build its first line. But I'm sure glad they did because it's allowed them so much political support to push forward with the system they are installing now. While even that had its fits and starts as well as issues with general managers and vehicle orders, I firmly believe that this will be the most European system in the United States when completed.

North Corridor Construction

Unlike any other LRT system in the United States, they eschewed existing freight rights of way and made the conscious decision to run in the major corridors with dedicated guideways. This is going to bring unprecedented mobility to the newly served areas as well as perhaps a few issues as well.

While many say that Houston has no zoning, what it really means is that Houston has no use restrictions. Unless your neighborhood has existing deed restrictions, anything is fair game as long as it pencils in your pro-forma. Making that pro-forma more difficult is all of the setback and parking regulations that are required from the city. It costs a lot of money and changes development dynamics but the lack of use restrictions allow development such as the housing below. Townhouses on small lots that would never have been allowed in any other single family neighborhood.

Southwest Corridor in East Downtown (EDO)

This also raises the issue of affordable housing. While the lack of building restrictions keeps prices fairly low, extremely low in fact when compared to SF or NYC, it doesn't mean that neighborhoods won't see some drastic changes coming to their neighborhoods.

If you would like to see a few more of the images from the trip, check out my Flickr page

Silicon Valley's Transit AND Land Use Problems

There's been a lot of bashing of Silicon Valley lately. It's the butt of transit jokes because of its light rail line which is one of the least traveled LRT lines in the United States for its distance and service. At the time it was built, it was one of the first new non legacy lines in the country. Now that shouldn't be an excuse but we certainly know that in order to be successful you have to connect people with the places they want to go in a timely fashion. The 1st street line connects a lot of places, but it does it rather slowly.

So we would hope they learned from that mistake when they were planning BART and actually decide to connect places, but give people a faster option, but they decided to double down with aweful all in the same of saving money. Sure they are saving money using existing ROW for BART, but they are also skipping destinations they need to connect to make it successful.

Light Rail is Dark Purple, Caltrain is Red, Plannded BART is Steel Blue, Green are areas of high employment density.

You can see that the planned BART line skips all of the North Valley tech employment and instead makes people depend on a slow light rail system to connect. Even when BART is complete to Berryesa, it won't be as effective as it would have been going under or through this employment cluster into downtown. Yes it would have cost more but the investment would have been there for hundreds of years.

Additionally, as I've mentioned in previous posts (1, 2), when silicon valley does get dense, it's in horrible suburban layouts. You can see below along the San Jose LRT line how buildings suck ridership right out of the system with parking and bad design.

So we would hope they learned from that mistake when they were planning BART and actually decide to connect places, but give people a faster option, but they decided to double down with aweful all in the same of saving money. Sure they are saving money using existing ROW for BART, but they are also skipping destinations they need to connect to make it successful.

Light Rail is Dark Purple, Caltrain is Red, Plannded BART is Steel Blue, Green are areas of high employment density.

You can see that the planned BART line skips all of the North Valley tech employment and instead makes people depend on a slow light rail system to connect. Even when BART is complete to Berryesa, it won't be as effective as it would have been going under or through this employment cluster into downtown. Yes it would have cost more but the investment would have been there for hundreds of years.

Additionally, as I've mentioned in previous posts (1, 2), when silicon valley does get dense, it's in horrible suburban layouts. You can see below along the San Jose LRT line how buildings suck ridership right out of the system with parking and bad design.

The last image above below shows how many buildings you could fit in this space if they had better non auto oriented design. And I guarantee this would drive ridership along the line.

Now there have also been discussions of how Silicon Valley needs to become Manhattan in order to keep talent that wants to live in urban places instead of valley sprawl. An article in the Awl made this claim but in reality, Silicon Valley doesn't need a hefty core of ultra tall buildings, it just needs to use the space it has better and become the DC or Paris of the Western United States. There's so much opportunity, yet it is completely wasted.

So in my eyes the transit is part of the problem for not making the connections that increase property values to do this type of infill, but its also the fault of developers who don't understand that a classic way of building for pedestrians is needed to attract pedestrians and quality of life that people are moving to San Francisco to attain. Sure some people don't want that, but we have more than enough supply of single family homes if there's more of a choice.

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Austin Route Choice Part 3: The Guadalupe/Lamar Alignment

In the previous two posts we discussed the history of Austin's quest for

rail transit and the possible political reasons behind the current urban rail

alignment. Finally we're getting to what I feel is the most important

part of this series which is making the case for the first urban rail alignment

that Austin should undertake.

The reason why I believe that the Guadalupe/Lamar alignment should be the first one is for political and practical reasons. Many pro-rail folks have written about this issue in the past 8 years so this ultimately is my way of putting more data behind those pushes. Let's go over why-

Political Future

Since 1995 Austin has had a hard time pushing forward with rail because of the politics. Most of the time the state or rail opponents were trying to take money from Capital Metro and put it into roads. Currently the city hasn't been able to drum up enough support to decide how to fund expansion or to have another election since the 2004 win. Given it took 6 years to build the Red Line through fits and starts as well as technical issues, it seems like it will continue to be a hard road until a blockbuster line is constructed.

We saw this in other cities as well. In places like Houston, the opponents such as Rep Culbertson and others have hammered away at the agency, trying to stop rail expansion at all corners. However, because the initial line was so successful (40K Riders a day) even the ouster of a General Manager and a house cleaning at Houston Metro has not delayed expansion and three extensions are currently under construction. In the Twin Cities, Charlotte, and Phoenix, initial lines were successful as well and extensions are pushing forward even through tough political climates. This is the reason why a first line with killer ridership is important. If you can silence the critics with a quality product, neighborhoods will be asking for extensions instead of opposing them.

Mining Existing Success

According to Metro's 2010 Service Plan 2020 report, the three highest ridership bus lines in the city are the #1 (14,912), the Forty Acres UT Campus Route (8,027), and #7 (7,725). The #1 and #7 are north-south routes that run from dense North Austin neighborhoods through UT, the State, and Downtown Austin. The #1 specifically and its express bus compatriot the #101 garner over 17,000 riders a day. That is a respectable number on most major corridors in medium size cities around the United States but at over double any other corridor in the city, it should stand to reason that a dedicated right of way rail line would be a great success. The map below shows line ridership from this report. It also shows the living density of downtown workers. The red lines are the 1,7, and Forty Acres Loop. Employment data was obtained from LEHD's On the Map program which uses 2010 data.

Where the People Are

Another thing the map above shows is where people who work downtown, at the University, and at the Capital Complex live in greater densities. The dark purple areas are those which house higher concentrations of Austin's core employees. Many of the people who are working in the densest employment center in the region are coming from North of the employment cluster, not east where the Urban Rail Line would run. Additionally, if we're looking for additional ridership, the gross intensity of residents plus workers is highest along the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor as seen in Orange below. Census tracts in dark green have more than 20 people per acre. This is ridership gold.

Congestion Issues on Guadalupe/Lamar

The corridor I believe should have a dedicated right of way also has a congestion issue. Given the limited number of direct north-south arterials that go through the center city, this is a significant problem. A TTI presentation on congestion made at the February 2012 (Item 3 19:45 into the presentation) transit working group meetings intimated that Guadalupe/Lamar from 6th street to 45th street is the most congested arterial in the city. In that same meeting, Dave Dobbs mentioned the fact that NEPA documents stated that the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor was at capacity for the last two decades. The same can not be said for the east corridor leading towards the Mueller redevelopment.

But why plan a non-dedicated right of way Rapid Bus for a corridor that has extreme congestion, especially at rush hour when people are leaving work and campus? Anyone who lives in Austin can tell you that Guadalupe from MLK to Dean Keaton is a nightmare at rush hour, moving at a snail's pace. Data from the Service Plan 2020 report suggests that the #1 bus already suffers from some of this congestion itself. In fact it is only on time 49.4% of the time. 49.4% That ranks the line 51st out of all the bus lines in Austin in on-time performance. Most of the time the line is too early. But if you look at the data, the bus is late almost 20% of the time. This is certain to affect a Rapid Bus, even with signal pre-emption and fancy stops.

And there's this problem, as much as road warriors would like to, you can't expand the road. None of the North South arterials are going to magically expand. With mixed use VMU coming down the pipeline bringing much needed densification, the need to move more people efficiently on the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor is going to be necessary, and welcome. Putting more buses on the corridor isn't going to help anything other than create bunching. Giving people an alternative that takes about the same amount of time every day is an important way to raise transit ridership as well as urban densities that create livable communities. The City of Austin seems to understand what Urban Rail would do for a corridor as shown below, however they seem to be ignoring the best corridor for this type of intervention.Why isn't Guadalupe/Lamar the target for this type of intervention?

City of Austin via Downtown Austin Alliance

This is why a dedicated right of way light rail line with significantly

greater capacity is necessary on this corridor. It would be nice to have

out to Mueller but outside of the density bonus, why do it? There's no

congestion there. There's not as much demand for service there. And

you're not going to get a ridership bang there that will give the region the

political capital to build extensions fast. My guess also is that more

people have ridden the #1 bus for its utility in Austin than have ridden the

#20.

The map below looks at the areas where downtown workers live and boardings. Again using LEHD On the Map data and shapefiles from Capital Metro showing 2012 weekday boardings (Thanks JMVC and Capital Metro). You can see that the Guadlupe/Lamar corridor has heavy boardings all the way up as do other parallel corridors moving north. This is where the demand is coming from for trips. Riverside looks pretty good as well.

Another thing you can spot from this is that where the dark purple is located, the boardings are heavier. This is because the density of people that work at UT, Downtown, or the Capital is higher in those places. Since downtown is constrained, more people are going to opt for the bus. The same can't be said for other areas that are easily accessed.

Goals for the System

A memo outlining goals and evaluation criteria for selecting the first segment of the Urban Rail system sent to the City Manager discusses the goals that the line should accomplish. Mueller certainly is pointed out as the goal corridor but let's go over some of the points here and reference back with what we discussed in this and earlier posts.

Evaluation Criteria

Provide Greater Mobility Options

1.1 Serve Existing Ridership - I hope we made the case with the maps and analysis of Capital Metro's ridership data that existing ridership is on the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor. The number 20 Manor bus gets 1/3rd of the ridership that the #1 corridor does. Additionally, the segment extensions from the edges of UT are approximately the same length from Cresview to 27th as the Mueller alignment (4 miles) The current ridership on those segments is ~3,300 on the Lamar Guadalupe Corridor to Crestview and only ~600 between San Jacinto and Mueller.

1.2 Serve New Ridership - New Ridership at Mueller is likely since the project hasn't been built out completely. However ridership on the #1 will go up because a rail line is a much more attractive option now for downtown commuters, especially in a dedicated right of way. UT students are already on the hook, but those who would use the line to go to the State or downtown would increase.

1.3 Support Other Modes - Nothing will support walking and biking more than building greater densities on the Lamar/Guadalupe corridor. The problem with the Mueller Corridor is the freeway barrier that exists. Once passing under the great wall of former East Avenue, any connections via bike or walking to the major destinations on the West side are lost to novice cyclists and walkers.

1.4 Provide Park and Ride Opportunities - If you take the Lamar/Guadalupe line north to the North Lamar Transit Center, you already have an existing park n ride. No need to buy new property and it could serve as a place for the maintenance bay as there is industrial land approximate.

Provide Access and Linkages Between Major Activity Hubs

2.1 - There are more activity hubs on the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor north of the core than east of it. This is proven by the existing ridership. People have places to go. Mueller is a wonderful place I'm sure but unlikely a major destination for students or Austin residents who don't live in the neighborhood. However on Guadalupe there is Amy's Ice Cream, HEB's Central Market, and Changos. Not to mention all those Hospitals, State Offices, and the Triangle. Those seem less important than good food to me. ;)

You can see how this works from this route rendering from aerial photos from Austin's skyscraper page.

But we're not even mentioning the core route, which on the first posts maps show all the parking garages and stadiums the line will pass. Not the actual buildings people work in or attend classes. I'm not really opposed to either of the alignments downtown, though west is likely faster through the core, but north and east of UT is what we're concerned about the most. Again I have no quibble with the Riverside segment as it works pretty well. There probably isn't a need to go to the airport but whatever helps people coming in for SXSW, ACL, or Texas Relays helps.

Improves Linkages Between High Capacity Modes

3.1 Connect to Red Line - Do it further north so there is no backtracking and people can get to more destinations. A commuter line that only runs every 30 minutes can't possibly be termed high capacity. It does have a high capacity vehicle. But if it doesn't go very frequently, then it isn't carrying a high capacity on that corridor. But you could connect with the rail line further north at say Crestview station. Then people won't have to backtrack and will have a two seat ride (while not ideal, it is better) to anywhere on the great Lamar/Guadalupe corridor.

There is a proposal to connect to the Red Line at Hancock Center. This would probably be better than the MLK or downtown alternatives, but Red River is a fairly narrow street which makes it difficult. Ultimately students would love to use the line to go to Freebirds and HEB but outside of commute times its not much of a destination corridor.

3.2 Connect to Lone Star Rail - Is that going to get done in anyone's lifetime?

3.3 Connect to Metro Rapid. - You'd be replacing most of Metro Rapid because there is a better mode for the corridor, urban rail. Metro Rapid was just a trick to get the FTA to pay for colored buses and new stops with fixed guideway funding. This type of purchase is happening around the country and is really starting to bother me as I believe this funding in the New Starts funding pot shouldn't be for Rapid Bus, it should be for actual fixed guideway projects like BRT, Streetcars, and Light Rail. Agencies should be building Rapid Bus lines, but there are funds for that as well.

3.4 Connect to ABIA - Again, no problems with the riverside segment

Improve Person Moving Capacity

4.1 Break Through Ring of Constraint Intersections - Mueller is better than the most congested arterial in the region as a destination for creating new corridor capacity? A Guadalupe/Lamar alignment would do this better than any other corridor. And if downtown streets have been at capacity since 1992 as this Statesman Article suggests, then why are planners shying away from the corridor that the most downtown workers are coming from as shown in the maps?

Additionally, looking at a Downtown Austin Alliance presentation from City of Austin Transportation officials, it's clear that the ring of constraint intersections broken through by the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor are more than the Mueller Alignment. There is proximity to three of the gateway intersections as seen below (38th and Guadalupe, 38th and Lamar, 24th and Guadalupe) while the Mueller alignment has one. And given the congestion on the corridor and existing ridership, it doesn't make sense to leave it out. Again, the Rapid Bus plan adds more seating capacity, but that doesn't mean travel time savings if the road is congested, the buses can't go anywhere.

Support City's Planning Goals

Check

Encourage Investment and Economic Development

6.1 Maximize Return on Investment and Development Opportunities. - Outside of Mueller I'm not sure where this applies more than on the North Lamar/Guadalupe corridor. There are so many opportunities to the north to change land uses and fix existing development patterns to support rail. Just north of the Triangle is a perfect example. That area could become a huge example of neighborhood redevelopment.

6.2 Maximize Economic Activity - No better place to raise sales tax receipts than to give people access to Amy's, Central Market, Chango's, Toy Joy, Mangia, Trudy's etc etc. Again, this is a destination corridor, unlike Mueller which has some opportunities, but not enough to be a first blockbuster investment.

6.3 Maximize Partnership Opportunities - Another metric for a small segment of right of way that will be used in Mueller. There's also a greater chance of joint development opportunities in the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor because there are more development opportunities period and likely a greater market for redevelopment. We are already seeing dense development taking place up through 32nd street. The expansion of the line will extend the mixed use possibilities.

6.4 Access to Jobs - There is no way that the Mueller corridor has more jobs than the North Lamar/Guadalupe Corridor. Additionally, we showed above in the maps that the corridor that will serve the most downtown workers is to the north, not to the east. For refreshment:

6.5 Potential for Job Creation - This goes back to the politics post. If they want to redevelop the parking lots, and get a UT Medical school, then the east alignment is what will help them do it. However if this is going to be a criteria, they should ding it for not connecting existing jobs and classrooms along the norther corridor.

Practical Considerations

7.1 Cost Effectiveness - The alignment through Mueller is approximately 4 miles. The Guadalupe/Lamar alignment to Cresview station is approximately 4 miles straight. Less curves less cost. Also, because more people will ride the corridor to the north, the cost effectiveness is going to be much higher on that 4 miles than it will be sending it to Mueller. We know this because of existing ridership on the corridor. Boardings between the University at San Jacinto through Mueller currently stand at ~600 as mentioned above. Boardings between the University at 27th and Crestview currently stand at ~3,300 . The North Corridor has over THREE TIMES the amount of boardings already. This means more riders and greater line productivity for the cost. Again the ridership map:

7.2 Maximize Competitiveness for FTA and Other Funding - The north corridor

already got a high rating the last time it was sent to the FTA (albeit it went to Howard Lane), why is the city

afraid of submitting it again? This is what I don't get. Why is everyone

in Austin so afraid of the Guadalupe/Lamar corridor for light rail. It

WON in 2000 inside the city of Austin. Not only did it win voters, in won

the FTA. What makes the

city think an inferior corridor will do better? And why isn't the city

following Houston's lead and running the line right through the center of its

major employment districts???

Here's Houston's alignment that has garnered so many riders:

And here are the alignment choices from Austin, again from skyscraper page

So after all of this what are the key points that should be made in regards to a Guadalupe/Lamar vs Mueller alignment?

1. Higher ridership and more useful lines have a greater ability to build political will for extensions.